Tuesday, June 28, 2005

Annual Time

Well, it's that time of year again - the time when airplane owners cringe in fear and prepare to burn the checkbook. Yellowbird is in for her annual checkup. I dropped her off last night at the shop at Turners Falls, and since I'll be away for a few weeks, my mechanic will have plenty of time to examine her. While she's in, I'll have a few minor squawks fixed, such as a couple of loose rivets in the cowling, and a worn carburetor intake duct. It's a shorter list than last year, so I'm hoping for the best. After getting a new muffler and attitude indicator, and with a new transponder in the works, she's been an expensive girl this year. I hope she appreciates the care she receives.

Well, it's that time of year again - the time when airplane owners cringe in fear and prepare to burn the checkbook. Yellowbird is in for her annual checkup. I dropped her off last night at the shop at Turners Falls, and since I'll be away for a few weeks, my mechanic will have plenty of time to examine her. While she's in, I'll have a few minor squawks fixed, such as a couple of loose rivets in the cowling, and a worn carburetor intake duct. It's a shorter list than last year, so I'm hoping for the best. After getting a new muffler and attitude indicator, and with a new transponder in the works, she's been an expensive girl this year. I hope she appreciates the care she receives. Turners Falls is a quiet little one-strip airport on the Connecticut River, about 30 miles north of Westfield, where Yellowbird lives. Her mechanic was recommend by Faithful Instructor George, who has his Skyhawk and Citabria worked on by the same shop.

Turners Falls is a quiet little one-strip airport on the Connecticut River, about 30 miles north of Westfield, where Yellowbird lives. Her mechanic was recommend by Faithful Instructor George, who has his Skyhawk and Citabria worked on by the same shop. Pioneer Aviation is a pleasantly rustic country FBO. Cub in the hangar and another taildragger in the pattern made for an idyllic scene on a quiet summer evening.

Pioneer Aviation is a pleasantly rustic country FBO. Cub in the hangar and another taildragger in the pattern made for an idyllic scene on a quiet summer evening. The maintenance hangar is a bit more modern. This is my girl about to go under the knife prior to last year's annual.

The maintenance hangar is a bit more modern. This is my girl about to go under the knife prior to last year's annual.We'll both be away for a few weeks, so blogging will be scarce. In the interim, here are a couple of my favorite photos from last year.

At 6,500 ft, above a hazy summer sky, we enjoyed this sunset coming back from our first major cross country adventure. From Westfield to Portsmouth, then to South Albany, and finally Cooperstown. Our return took us to Portsmouth again to drop off a friend, and then back home.

At 6,500 ft, above a hazy summer sky, we enjoyed this sunset coming back from our first major cross country adventure. From Westfield to Portsmouth, then to South Albany, and finally Cooperstown. Our return took us to Portsmouth again to drop off a friend, and then back home.Monday, June 20, 2005

Beating the Transponder Gremlin

Yellowbird's transponder gremlin has had a lengthy but unwelcome residency. He's been there at least since I met Yellowbird in February of 2004. The ferry pilot who delivered her noted some problems with the transponder, despite her just having passed her biannual transponder check the previous month. As Yellowbird and I got to know each other, we sometimes experienced problems with her identity, including incorrect squawk codes, intermittent transponder responses, and occasional mode C errors. Twice I took her to the Radio Shop at Worcester to have things checked, and both times everything checked out fine, but still the problems persisted. It was bad enough that I was hesitant to request radar advisories or fly in class C or B airspace.

Yellowbird's transponder gremlin has had a lengthy but unwelcome residency. He's been there at least since I met Yellowbird in February of 2004. The ferry pilot who delivered her noted some problems with the transponder, despite her just having passed her biannual transponder check the previous month. As Yellowbird and I got to know each other, we sometimes experienced problems with her identity, including incorrect squawk codes, intermittent transponder responses, and occasional mode C errors. Twice I took her to the Radio Shop at Worcester to have things checked, and both times everything checked out fine, but still the problems persisted. It was bad enough that I was hesitant to request radar advisories or fly in class C or B airspace.The last straw came a few weeks ago when we were scolded out of the sky by Bradley approach while practicing ILS approaches. The transponder's antics were annoying them so much that they asked us to land and not bother them again until the transponder was fixed. Back to the shop we went and a temporary replacement transponder was swapped for the bad one. We went up again a few days later for more practice, and this time we only had a faulty mode C reading. That was enough to end that day's lesson, and arrangement were made to get back to Worcester to have the altitude encoder looked at. The weather didn't look good for the rest of the week, but the Transpondoctor was willing to try his best as soon as we got a chance to visit again.

That chance came earlier than expected, as Friday's weather defied a gloomy forecast. We arrived at the shop at the appointed time and Dr. Squawk set up his equipment. This included a test apparatus I had seen before, consisting of a transponder test box with a remote antenna. The antenna was set up close to Yellowbird's transponder antenna below the baggage compartment, and when turned on, it confirmed that the transponder was communicating appropriately. A second piece of test equipment comprised a magic box containing assorted air pumps and valves, as well as the three standard pitot/static instrument: airspeed indicator, altimeter, and vertical speed indicator. This was connected to Yellowbird's static system, and when activated, it would adjust the air pressure to simulate the environment at a desired altitude.

With the transponder transmitting the altitude, the good Doctor worked the magic box to take Yellowbird up to a simulated 3,000 feet. As the altimeter on the magic box ascended, the mode C readout on the transponder test box echoed the altitude. Holding level at 3,000 ft, everything seemed fine. On a hunch, the Doctor began thumping the side of the encoder. Each time he thumped, the mode C readout on the transponder test box would flicker. When he stopped, it read steady at 3,000 ft. He thumped some more, the digital readout flickered again, and after a few seconds, it suddenly dropped to 2,500 ft. and stayed there. The altimeter on the magic box still showed 3,000 ft. It appeared that we had found our gremlin.

A replacement encoder was produced, and a few minutes with a screwdriver saw the transplant completed. Again, the boxes were hooked up and the air pump chugged gently and took us back up to 3,000 ft. Watching the slowly ascending needle and the corresponding digital readout, I was reminded of the scene in Apollo 13 where the mission controllers anxiously watch the telemetry data coming from the crippled Service Module, hoping that the oxygen leak can be stemmed by shutting down the fuel cells.

In our case, we reached 3,000 ft again with no problems. Again, the Transpondoctor thumped. Again the readout flickered. And again it dropped suddenly to 2,500 ft. I knew that Yellowbird wasn't going to be trapped in lunar orbit, but imagining the imminent slow leak of money from my bank account gave me a similar sense of foreboding. But the Transpondoctor, with many years of practical experience, saw something that I hadn't. Below the digital readout on the transponder test box was a group of about a dozen LED lights, apparently one for each wire in the harness connecting the encoder to the transponder. As the altitude changed, each 100 ft. increment was indicated by a different combination of lights as the encoder translated the altitude to a binary code. As he thumped and observed the flickering display, he noticed that one light in particular was prone to cutting out. Crawling under the panel, he probed at the wiring harness until he found the corresponding wire. One tug told him all he needed to know. He disassembled the connector plug at the encoder end of the harness and confirmed that the solder joint had failed leaving only the tight confines within the connecter to keep the wire in contact with the plug. Five minutes with a soldering iron set things to rights, and with the original encoder reinstalled, we ran the test again. This time the altitude held steady throughout even the thumps.

We were back in the air less than an hour after we had arrived. With a freshly soldered connection, Yellowbird seemed a bit more sprightly than usual, and I let her romp around a bit among the scattered cumulus. Over the weekend we spent nearly two and a half hours shooting approaches at Westfield and Westover, with no complaints from Bradley. The loaner transponder has done well so far, but once next month's annual is out of the way, we'll be getting a permanent replacement. Yellowbird at last has a healthy sense of self, and we can confidently contact ATC without fear of rejection. As for the gremlin, who knows where he has been hiding. He was last seen eying a large mallet at an undisclosed Air Force base, apparently up to no good.

We were back in the air less than an hour after we had arrived. With a freshly soldered connection, Yellowbird seemed a bit more sprightly than usual, and I let her romp around a bit among the scattered cumulus. Over the weekend we spent nearly two and a half hours shooting approaches at Westfield and Westover, with no complaints from Bradley. The loaner transponder has done well so far, but once next month's annual is out of the way, we'll be getting a permanent replacement. Yellowbird at last has a healthy sense of self, and we can confidently contact ATC without fear of rejection. As for the gremlin, who knows where he has been hiding. He was last seen eying a large mallet at an undisclosed Air Force base, apparently up to no good.Friday, June 17, 2005

Round-Engined Goodness

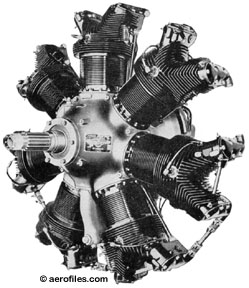

I was at the airport the other evening, washing bugs off the Yellowbird, when I heard a distinctive sound coming from midfield. It was something between a growl and a rumble and a throb, and it echoed off the nearby hangars until it was difficult to tell exactly where it came from . I knew at once what it was. It was a sound that once filled the skies of America, particularly in the south and west, but which is rarely heard these days. It was the sound of a radial engined aircraft. Most air-cooled piston engines in use today are of the horizontal-opposed type, like Yellowbird's Lycoming O-360, but radial engines once powered a large percentage of propeller driven aircraft. Their reputation for durability and low power to weight ratios (compared to liquid-cooled engines) made them popular with aircraft designers from the early days of aviation up until the 1950's and 1960's, when the increased complexity of high-powered radial engines encouraged their replacement by newly developed turboprop engines capable of even greater power at lower weights. Today, very few airplanes still fly with radial engines, and most of those are rarely seen outside of air shows. If you're lucky, you might catch one in the pattern on a quiet summer evening, keeping the rust and cobwebs away. The other evening, I got lucky.

Most air-cooled piston engines in use today are of the horizontal-opposed type, like Yellowbird's Lycoming O-360, but radial engines once powered a large percentage of propeller driven aircraft. Their reputation for durability and low power to weight ratios (compared to liquid-cooled engines) made them popular with aircraft designers from the early days of aviation up until the 1950's and 1960's, when the increased complexity of high-powered radial engines encouraged their replacement by newly developed turboprop engines capable of even greater power at lower weights. Today, very few airplanes still fly with radial engines, and most of those are rarely seen outside of air shows. If you're lucky, you might catch one in the pattern on a quiet summer evening, keeping the rust and cobwebs away. The other evening, I got lucky. What I heard, and then saw directly overhead on a left downwind for 33, was a Fairchild PT-23A, the radial engine version of the PT-19 trainer from World War II. This PT-23 is locally based, and I've seen it in the skies before, but never up close. For a few moments, I reveled in the unique music of its seven-cylindered Continental engine as it trundled overhead. Then I cursed myself for leaving the camera at home. I rushed home to get it, hoping to catch him in action before he came back down, but as I pulled into the FBO parking lot, I saw that the evening's airshow was coming to a close. I settled for finding an advantageous spot on the ramp to watch him as he taxied back to his hangar.

What I heard, and then saw directly overhead on a left downwind for 33, was a Fairchild PT-23A, the radial engine version of the PT-19 trainer from World War II. This PT-23 is locally based, and I've seen it in the skies before, but never up close. For a few moments, I reveled in the unique music of its seven-cylindered Continental engine as it trundled overhead. Then I cursed myself for leaving the camera at home. I rushed home to get it, hoping to catch him in action before he came back down, but as I pulled into the FBO parking lot, I saw that the evening's airshow was coming to a close. I settled for finding an advantageous spot on the ramp to watch him as he taxied back to his hangar. As he rolled past, he cut the engine and coasted in with the prop stopped. Taildraggers are said to be tricky to handle on the ground, but I was treated to a fine display of parking as he deftly applied the right brake and spun around to stop directly in front of the hangar door.

As he rolled past, he cut the engine and coasted in with the prop stopped. Taildraggers are said to be tricky to handle on the ground, but I was treated to a fine display of parking as he deftly applied the right brake and spun around to stop directly in front of the hangar door. As the crew packed up for the night, I took some time to chat with them and examine the old girl. She's been beautifully restored in authentic wartime markings. Every square inch of her wooden wings and fabric covering spoke of careful attention to detail. It was a treat to see such a rare airplane so well cared for. I knew the pilot by reputation, having some common acquaintances, but I had never met him in person before. He was happy to share with me as I asked any questions that came to mind, and I was delighted at the opportunity to meet him and his airplane.

As the crew packed up for the night, I took some time to chat with them and examine the old girl. She's been beautifully restored in authentic wartime markings. Every square inch of her wooden wings and fabric covering spoke of careful attention to detail. It was a treat to see such a rare airplane so well cared for. I knew the pilot by reputation, having some common acquaintances, but I had never met him in person before. He was happy to share with me as I asked any questions that came to mind, and I was delighted at the opportunity to meet him and his airplane. Here's 668 cubic inches of pure radial goodness. Surprisingly, she only has 40 more horsepower than Yellowbird does, but she puts it out with a glorious sound that gives the impression of much more power. Oh, to live in the age of round engines and cloth helmets! For now, it's good to live next door to an airport where such things can still be found. This round engine flies frequently, the pilot has my phone number and an open invitation has been extended - I may get even luckier...

Here's 668 cubic inches of pure radial goodness. Surprisingly, she only has 40 more horsepower than Yellowbird does, but she puts it out with a glorious sound that gives the impression of much more power. Oh, to live in the age of round engines and cloth helmets! For now, it's good to live next door to an airport where such things can still be found. This round engine flies frequently, the pilot has my phone number and an open invitation has been extended - I may get even luckier...Update:

If you like airplane engines, round, square, or triangular, you might want to visit the Aircraft Engine Historical Society. Their website has many cubic inches of fascinating information on airplane engines, including historical and engineering articles, photographs, and even sound recordings of these amazing engines.

(The W-670 photo is hosted on AeroFiles.com.)

Wednesday, June 15, 2005

A Visit to the Transpondoctor

Yellowbird has always had a bit of an identity problem. Specifically, her transponder has been intermittently intermittent at least since I bought her. Even the pilot who delivered her had problems. At times it would read correctly, but sometimes ATC would report the mode C as being either dramatically off or missing altogether. I've had a few times where ATC reported an incorrect squawk code, and even once where they told me that they were picking up two different squawks, one digit apart. Like any good pilot, I assumed that if I ignored the problem, it would eventually go away. Gremlins really only want attention, and if they don't get it, they will usually move to someone else airplane. Unfortunately, my transponder gremlin decided that if I wasn't going to pay attention, it would appeal to a higher authority.

Yellowbird has always had a bit of an identity problem. Specifically, her transponder has been intermittently intermittent at least since I bought her. Even the pilot who delivered her had problems. At times it would read correctly, but sometimes ATC would report the mode C as being either dramatically off or missing altogether. I've had a few times where ATC reported an incorrect squawk code, and even once where they told me that they were picking up two different squawks, one digit apart. Like any good pilot, I assumed that if I ignored the problem, it would eventually go away. Gremlins really only want attention, and if they don't get it, they will usually move to someone else airplane. Unfortunately, my transponder gremlin decided that if I wasn't going to pay attention, it would appeal to a higher authority.For the past month or so, Faithful Instructor George has been enduring my attempts to master the intricacies of instrument flying. The last two instrument lessons were filed as IFR so that we could do some approaches at KBAF. We had been with Bradley approach for only a few minutes on the first lesson last week when they asked us to confirm our altitude. We had been cleared to 4,000 feet, but had overshot by about 500 feet and was wandering up and down as I tried to get trimmed for level flight amongst the thermals of a warm humid afternoon. I sheepishly reported that I was returning to 4,000, but the tower replied that they had our mode C indicating 1,100.

The mode C issue of last week's lesson was only the beginning of troubles. We reset the transponder to no avail, and then turned off the mode C. From then on, ATC frequently asked us to confirm our squawk code, and finally asked us to change to a similar code of one digit's difference. We had both copied the same code when we got our clearance, so we wondered if maybe ground had given us the wrong code, but our next lesson was to dispel that suspicion.

This time, Bradley immediately started to question our squawk. They didn't report any mode C issues, but they told us that they were getting multiple hits off our transponder, with different codes, and that we were setting off all sorts of alarms in their system. We had planned on three approaches, and while vectoring us for the third, they got sufficiently fed up to tell us to make it a full stop and don't come back up until we got the transponder fixed. We were going for a full stop anyway, so we landed and concluded the lesson.

Yellowbird has been to Worcester to see the transpondoctor twice in the last 12 months to have this issue looked at, and both times, the transponder and its fittings checked out perfectly on the ground. Still, he cleaned the connections and re-racked the transponder just to make sure that it wasn't a case of dusty electrical connections. If that didn't clear things up, his next trick would be to temporarily replace the transponder with a fresh unit of the same model. After being scolded out of the sky by the Bradley controller, we didn't have a choice.

Yesterday Yellowbird and I braved the bumpy skies for the short trip over to Worcester for a third visit. The afternoon thunderstorms had moved east, leaving low ceilings and plenty of turbulence, but we still had decent VFR conditions. At Worcester, the transpondectomy involved nothing more complicated than sliding the old unit out of its rack and sliding a replacement in to take its place. I'll fly for a few weeks with the replacement. If I still have problems, we'll know to look for another solution. If not, then Yellowbird will be getting a new transponder.

Yesterday Yellowbird and I braved the bumpy skies for the short trip over to Worcester for a third visit. The afternoon thunderstorms had moved east, leaving low ceilings and plenty of turbulence, but we still had decent VFR conditions. At Worcester, the transpondectomy involved nothing more complicated than sliding the old unit out of its rack and sliding a replacement in to take its place. I'll fly for a few weeks with the replacement. If I still have problems, we'll know to look for another solution. If not, then Yellowbird will be getting a new transponder.Update:

We went up for another instrument lesson this evening. We had no apparent problems with the transponder's squawk, but the mode C, which checked out fine on the way back from Worcester, was now reading about 1,000 ft low. The weather is supposed to be nicely IFR for a few days, so I may not get the chance to have this checked out for a while. Dang. At least I got in 20 minutes of actual, as well as my first ILS approach in IMC.

Sunday, June 12, 2005

Buy Me a Cardinal

Every aircraft is required by federal regulations to carry certain documents on board at all times. These include the airworthiness certificate, the aircraft registration, the operating handbook, and the aircraft's weight and balance specifications. A prudent aircraft owner will also obtain copies of the service manual and parts catalog to help in evaluating plans for ongoing maintenance. But the true airplane geek will go to great lengths to find original copies of the sales brochure and price list. These can be found on eBay for a reasonable price, and for those of us who fly older aircraft, they can be an interesting trip down memory lane as well as a revealing look at advertising practices of years gone by. In Yellowbird's case, we go all the way back to 1974. Fortunately, the general aviation market seems to have been spared some of the worst stylistic offenses of the 1970's, but there's still enough to make us thankful for the passing of years and fashions, even as we lament the all too short production run of our favorite Cessna.

Every aircraft is required by federal regulations to carry certain documents on board at all times. These include the airworthiness certificate, the aircraft registration, the operating handbook, and the aircraft's weight and balance specifications. A prudent aircraft owner will also obtain copies of the service manual and parts catalog to help in evaluating plans for ongoing maintenance. But the true airplane geek will go to great lengths to find original copies of the sales brochure and price list. These can be found on eBay for a reasonable price, and for those of us who fly older aircraft, they can be an interesting trip down memory lane as well as a revealing look at advertising practices of years gone by. In Yellowbird's case, we go all the way back to 1974. Fortunately, the general aviation market seems to have been spared some of the worst stylistic offenses of the 1970's, but there's still enough to make us thankful for the passing of years and fashions, even as we lament the all too short production run of our favorite Cessna.So, put on your powder blue leisure suit, grab the plaid pants-suited wife, and with a nod to James Lileks, come with me back to a time when avocado green was exciting, poor grammar in a professional business context was fashionable, and Cessna avionics cost about the same as they do today. Are you ready? Then...

Monday, June 06, 2005

How to Get to Carnegie Hall

A few months ago, I got a special e-mail invitation from my father. His church choir was to be part of a 300 voice chorus assembled for a performance of the Verdi Requiem by the Manhattan Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. I hadn't seen Dad since Thanksgiving a few years ago, and New York is only a few hours drive from Westfield, so I was eager to attend the concert. I've driven through NYC a few times on the way to points south, but I've never driven to the city, so I was unsure of the best way to get there. A few contacts yielded recommendations of driving to one of the nearby cities and taking the train into Manhattan, and the MTA website provided a list of potential stations with parking options, but I still felt that there had to be a better way. I had never flown Yellowbird to the New York City area, but this seemed to be a mission perfectly suited for her. Again, contacts yielded recommendations on airports to fly in to, as well as options for getting from the airport into Manhattan. Yellowbird was fueled up, and if the weather cooperated, we were ready to go.It was a rare springtime weekend that saw perfect flying weather for more than a few hours at a time. The threatened rain moved out of the area much earlier than forecasted, so we launched on schedule for a one hour flight. Teterboro was our destination, and we joined the busy stream of corporate jets for arrival. After parking, a short bus ride took me into Manhattan, and a short walk got me to Dad's hotel in time to join him and his wife and daughter for lunch. They had just finished the morning rehearsal, and they had the rest of the day off, so we set out to see the sights. The subway took us south to Ground Zero, and from there we went south to Battery Park. After wearing out our feet, we caught the 6:00 bus back to Teterboro, where I had prepared for some evening sightseeing.

A few months ago I attended an FAA seminar on flying the Hudson River VFR corridor, and armed with pages of notes, I prepared a kneeboard-sized itinerary listing altitudes, radio frequencies, and reporting points. The river has a reputation for confined airspace and heavy traffic, so I wanted to be as prepared as possible. As it turned out, the river traffic was very light, and I even had time to take a few photos along the way.

Southbound, approaching the George Washington Bridge at 900 ft. The Manhattan skyline is visible in the distance. It was a clear calm evening, and surprisingly quiet. We had the river to ourselves until this point northbound, when a couple of helicopters passed us heading south.

Southbound, approaching the George Washington Bridge at 900 ft. The Manhattan skyline is visible in the distance. It was a clear calm evening, and surprisingly quiet. We had the river to ourselves until this point northbound, when a couple of helicopters passed us heading south. Still southbound, abeam uptown Manhattan. The Empire State Building doesn't command the same presence it once did, but it still holds its own against a host of newer skyscrapers to the north. The Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum sits on the river at lower center.

Still southbound, abeam uptown Manhattan. The Empire State Building doesn't command the same presence it once did, but it still holds its own against a host of newer skyscrapers to the north. The Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum sits on the river at lower center. At the southern point in our tour, we turn around at the Statue of Liberty. The airspace is pretty tight here, with very little room between Liberty Island and the Newark class B airspace to the west. The GPS came in handy in keeping situational awareness.

At the southern point in our tour, we turn around at the Statue of Liberty. The airspace is pretty tight here, with very little room between Liberty Island and the Newark class B airspace to the west. The GPS came in handy in keeping situational awareness. The World Financial Center, with Ground Zero beyond. The only time I visited the WTC was in 1983, and that was at night. We took the subway then, so I never got to see the Towers from the ground. Still, it was an erie feeling to approach Ground Zero on foot. Apart from the memorials, there was no hint of what took place here. It was hard to imagine that the site was once buried under piles of smoking rubble. Most of the damage has been repaired, and the site looks like any large construction zone. Whatever they build here, the hole will always remain.

The World Financial Center, with Ground Zero beyond. The only time I visited the WTC was in 1983, and that was at night. We took the subway then, so I never got to see the Towers from the ground. Still, it was an erie feeling to approach Ground Zero on foot. Apart from the memorials, there was no hint of what took place here. It was hard to imagine that the site was once buried under piles of smoking rubble. Most of the damage has been repaired, and the site looks like any large construction zone. Whatever they build here, the hole will always remain. Over the Intrepid on a very high short final. Power to idle and full flaps just might get us down there. It's a good thing they parked all those airplanes on deck, or I'd be tempted.

Over the Intrepid on a very high short final. Power to idle and full flaps just might get us down there. It's a good thing they parked all those airplanes on deck, or I'd be tempted. Heading back to TEB, Dad gets a turn at the wheel. I took most of the rest of the family up in a rented Skyhawk in Houston at Thanksgiving last year. This trip filled out the family flight roster. Only my older sister, who balks at boarding anything with wings, has yet to fly with me.

Heading back to TEB, Dad gets a turn at the wheel. I took most of the rest of the family up in a rented Skyhawk in Houston at Thanksgiving last year. This trip filled out the family flight roster. Only my older sister, who balks at boarding anything with wings, has yet to fly with me.After returning to Teterboro, I dropped Dad and crew off at the FBO from where they were taken to the bus stop for their ride back to Manhattan. Yellowbird and I departed at dusk and had a beautiful night flight home. On Sunday morning, I departed again, with a friend along for the ride and concert. We repeated the route from yesterday, and after lunch in a small but excellent eatery, we took our seats in Isaac Stern Hall.

The concert itself was superb - the assembled choirs sang marvelously, and the Manhattan Philharmonic was absolutely stunning. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for Dad and crew, and I'll treasure the memory always.

The concert itself was superb - the assembled choirs sang marvelously, and the Manhattan Philharmonic was absolutely stunning. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for Dad and crew, and I'll treasure the memory always.As for getting to Carnegie Hall, that's pretty easy: From KBAF, take Victor 106 to the Pawling VOR, then direct to Teterboro. After landing, either walk to or have the FBO car drop you off at the New Jersey Transit bus stop at Rt. 46 and Industrial Ave. Take the #161 bus to the Port Authority Bus Terminal. From there, either take the E Train to 7th Ave, or ask any New Yorker and you will get proper directions.

Saturday, June 04, 2005

In Memoriam

June 4th marks the 63rd anniversary of the Battle of Midway, the decisive WWII battle which turned the tide of the war in the Pacific against the Japanese. Midway has been the subject of many books and a few motion pictures, so I won't go into the details of the battle other than to retell the basic details. In 1942, flush from victories across the Pacific, the Japanese set their sights on the American base at Midway Island. Seizure of the base would have given the Japanese a vital forward base from which to launch attacks against the American forces stationed in Hawaii. The invasion effort was supported by an impressive naval force of four aircraft carriers, seven battleships, and numerous cruisers, destroyers, and other vessels. To counter this fleet, the Americans offered three aircraft carriers, (one of which had been hastily repaired following damage received at the Battle of the Coral Sea) eight cruisers, an assortment of supporting destroyers and submarines, and a number of Army, Navy, and Marine aircraft based on Midway Island.

In 1942, flush from victories across the Pacific, the Japanese set their sights on the American base at Midway Island. Seizure of the base would have given the Japanese a vital forward base from which to launch attacks against the American forces stationed in Hawaii. The invasion effort was supported by an impressive naval force of four aircraft carriers, seven battleships, and numerous cruisers, destroyers, and other vessels. To counter this fleet, the Americans offered three aircraft carriers, (one of which had been hastily repaired following damage received at the Battle of the Coral Sea) eight cruisers, an assortment of supporting destroyers and submarines, and a number of Army, Navy, and Marine aircraft based on Midway Island. The battle unfolded across four days in early June, with most of the fighting occurring on June 4th. That day saw a remarkable succession of missteps, miscalculations, and strokes of luck, both good and bad, on both sides. The day opened with the Japanese holding almost all the advantages, but the events of that day worked out against them and nightfall saw their hopes shattered as all four of their aircraft carriers had been destroyed. The lion's share of the victory belonged to the pilots of the air groups operating from the American carriers, and particularly to the dive bomber pilots who planted their bombs squarely on the decks of the Japanese ships, and the crews of the torpedo planes who launched their attacks against impossible odds, paying a dear price in the process.

The battle unfolded across four days in early June, with most of the fighting occurring on June 4th. That day saw a remarkable succession of missteps, miscalculations, and strokes of luck, both good and bad, on both sides. The day opened with the Japanese holding almost all the advantages, but the events of that day worked out against them and nightfall saw their hopes shattered as all four of their aircraft carriers had been destroyed. The lion's share of the victory belonged to the pilots of the air groups operating from the American carriers, and particularly to the dive bomber pilots who planted their bombs squarely on the decks of the Japanese ships, and the crews of the torpedo planes who launched their attacks against impossible odds, paying a dear price in the process. The Americans suffered the loss of one aircraft carrier and one destroyer, as well as a large number of land and carrier based aircraft and crews. Considering the magnitude of the victory, it was a fairly light price to pay, and the American manufacturing and training efforts would more than make up for the loss in the years to follow. On the other side, the loss of four aircraft carriers, plus all of their aircraft and most of the aircrews, was a blow from which the Imperial Japanese Navy never fully recovered. And although the war was to rage for three more years, Japan was never able to regain the offense. The eventual American victory required further sacrifices at Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and a host of other places, but the seeds of that victory were planted by a small group of brave men who answered the call to duty on that day in June of 1942.

The Americans suffered the loss of one aircraft carrier and one destroyer, as well as a large number of land and carrier based aircraft and crews. Considering the magnitude of the victory, it was a fairly light price to pay, and the American manufacturing and training efforts would more than make up for the loss in the years to follow. On the other side, the loss of four aircraft carriers, plus all of their aircraft and most of the aircrews, was a blow from which the Imperial Japanese Navy never fully recovered. And although the war was to rage for three more years, Japan was never able to regain the offense. The eventual American victory required further sacrifices at Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and a host of other places, but the seeds of that victory were planted by a small group of brave men who answered the call to duty on that day in June of 1942.A Tribute

Before I met Yellowbird, my aerial adventures were limited to reading books on aviation history, and building models of whatever airplanes caught my fancy. I was actually very good at it, and I won enough awards at various model competitions to fill several boxes in the basement. One ongoing project, inspired by reading The Big E, Edward Stafford's biography of the USS Enterprise (CV-6), was to build a collection of models representing the aircraft flown by the various air groups that operated from the Enterprise during the war. The following three models from this collection depict aircraft flown by Enterprise Air Group during 1941/1942, and are presented here in honor of the bravery and sacrifice of those who fought at Midway.

Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless

Douglas SBD-3 DauntlessThe story of Midway is essentially the story of the SBD Dauntless. The SBD was the Navy's principal dive bomber at the beginning of the war, and although it was considered obsolete, it continued in that role until war's end in 1945. This model depicts an SBD-3 of Bombing Six flown by Ensign Frederick Weber on June 4th. Ensign Weber and his gunner, Aviation Ordnanceman Ernest Hilbert, were credited with one of three fatal hits on the Japanese carrier Akagi during the initial attack by American carrier planes. They returned safely to the Enterprise, but were shot down later that afternoon while maneuvering for attack on the carrier Hiryu. The 1/48th scale model was built from the Hasegawa kit with many details added, and represents 6-B-3 as she might have looked prior to her last mission.

Douglas TBD-1 Devastator

Douglas TBD-1 DevastatorThe sacrifice of the torpedo planes at Midway is an epic story of heroism. Unable to gain an advantageous attack position, and denied protective fighter cover, the torpedo planes pressed on with their low altitude attacks and were decimated by the Japanese fighter escorts. Their sacrifice was not in vain, for by drawing the attention of the Japanese defenses down to wave-top level, they allowed the American dive bombers to launch their high altitude attacks completely unopposed. The timing was purely accidental, but absolutely crucial to the outcome. The 1/48th scale model was built from the Monogram kit and represents a TBD-1 of Torpedo Six as it would have appeared at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat

Grumman F4F-4 WildcatDue to the urgency of battle, the American carrier planes faced a number of obstacles in carrying out their attacks. One of these was an unfortunate lack of coordination between the fighter escorts and the torpedo and dive bombers they were supposed to protect. As a result, the fighters made relatively little impact on the American offensive effort. They did provide essential cover for the American naval forces in the face of the Japanese air attacks that crippled the carrier Yorktown. This 1/48th scale model was built from the Tamiya kit and represents an F4F-4 from Fighting Six during May of 1942.

(Historical photographs are hosted by the Naval Historical Center)

Thursday, June 02, 2005

A Better Mood

Yellowbird was a few days on the ground sulking out her bad attitude indicator while I made arrangements to get her to the shop. Fortunate the wait was short and the following Friday afternoon allowed a quick trip to Turners Falls. My mechanic suspected that the shock mounts for the gyro panel might need replacing, so we started there. It wasn't an easy job, from the looks of it, but he managed to replace each of the four small rubber panel mounts without removing the panel itself. We then ran up the engine throughout the range where the vibration was occurring and had no problems. An hour and an hour's worth of labor, plus the cost of parts, and we were on our way home. She's been stable for the most part since then, although sometimes I see some vibration while cycling the prop during runup. My mechanic recommended getting the prop rebalanced, which has been on my nice-thing-to-do-someday list, so I'll move it up to the top of the list. Faithful Instructor George and I went up the next week for an instrument lesson under simulated conditions. He put me through the standard routine of Pattern A, steep turns, and recovery from unusual attitudes. After about four recoveries, George pulled out the Post-it pad and failed the attitude and heading indicators and we did a few more recoveries. He was really having a good time getting me disoriented, and when I looked up to recover from another unusual attitude, I noticed that he had drawn a smiley face on the Post-it covering the attitude indicator. It was a fun lesson.

Faithful Instructor George and I went up the next week for an instrument lesson under simulated conditions. He put me through the standard routine of Pattern A, steep turns, and recovery from unusual attitudes. After about four recoveries, George pulled out the Post-it pad and failed the attitude and heading indicators and we did a few more recoveries. He was really having a good time getting me disoriented, and when I looked up to recover from another unusual attitude, I noticed that he had drawn a smiley face on the Post-it covering the attitude indicator. It was a fun lesson.